**UPDATE** for more recent work related to sound and art please go to https://auditoryvisions.org/

What is your experience of walking through modern-day art galleries? As you pass from room to room are you fully engaged with the works on the walls or, despite all good intentions, does a sense of fatigue begin to dampen your enthusiasm?

Numerous factors provoke the wandering of the gallery patron’s mind: the scale of an exhibition may be too immense to comprehend in a single visit; the show may have been poorly curated or installed; external elements such as noise might distract the viewer’s focus. However one factor that receives little attention is the way in which galleries often cater to only one sense, the visual.

The schism between the senses is not a natural state of being. Although we regard vision as our primary means of negotiating the world it exists in relation to our other sources of perception. Sebastiane Hegarty writes about the synesthesia that naturally exists between the senses, stating “it is rare if ever that we perceive through the attention of one sense only. The senses perform in concert a ‘clump of sensation’ rather than distinct, independent and rarefied channels” . So is the disengagement we often feel in a gallery due to the intense channelling of one sense at the expense of others?

Perhaps it was this question that lead to a recent exhibition at the National Gallery in London where sound artists were invited to interpret paintings from its permanent collection. Renowned field recordist Chris Watson chose to interpret Constable’s “The Cornfield” by combining field recordings to represent elements from its pastoral scene. While viewing the work gallery patrons could hear the sounds of a dawn chorus, a fresh water spring, corn-heads swaying in a breeze, and distant church bells. This complementary use of field recordings enabled patrons to engage with the painting in a dynamic new way – the sounds heard before them guided their eyes across the canvas at details often overlooked or dismissed.

Inspired by this experience I began to produce my own series of interpretive soundscapes to the works of Australian artists. The first step in this process was to choose which works to interpret. After creating soundscapes to some early colonial paintings I finally decided to focus on the work of contemporary Australian print-makers. This focus would provide a sense of uniformity to the project.

One of the first prints I interpreted was Michael Schlitz’ “Sound of Moon B”. In this work Schlitz has created a series of parallel lines on a desolate white background. It is an imagined topography of the moon …

These soundscapes are best listened to with HEADPHONES

Listening to Michael Schlitz’s “Sound of Moon A and B”.

Sound of Moon B

Michael Schlitz is a Tasmanian print-maker whose work explores themes of isolation. Schlitz is often identified through his poignant depiction of crouched lone figures in dark forested areas. Sound of Moon A and B continue to examine this subject, this time within the openness of space. These prints portray a landscape physically removed from civilisation, a place to escape into an unearthly sense of calm. Yet the composition Sound of Moon B imagines the near side of the moon as a place still subject to earth’s noisy activities. Here sonic interference from satellites and radio communication reflect upon the moon’s surface.

Sound of Moon A

The human desire to fly is as old as the Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus. In this story Daedalus is imprisoned with his son Icarus in Crete. Unable to escape by sea Daedalus uses wax to fasten a pair of wings to Icarus’ shoulders. Daedalus instructs his son to fly neither too high nor too low. Not heeding his father’s advice Icarus flies upwards towards the sun, causing the wax to melt. Icarus plunges into the ocean and drowns. The moral of the story can be read in multiple ways: always listen to advice, be conscious of one’s own hubris, value moderation over excess.

This oil painting by Italian painter Carlo Saraceni, circa 1600, depicts the dramatic moment when Icarus falls. From the ground two men observe the scene, perhaps imagining the doomed father and son to be gods.

This is the second in what is to be a series of soundscapes focussing on birds in art. Wind becomes increasingly hostile to the figures in the sky. Moments of static fill the air. An antique auto-harp plays, grounding the piece in a bygone era.

Listening to Travis Paterson’s “Anchors Aweigh” “Land, ho!”.

Land, ho TP

Travis Paterson is a printmaker from NSW, Australia. Paterson’s work explores histories, both real and imagined, by sourcing imagery from old Primary School readers. Paterson is especially interested in the ways these images instruct and enforce masculinities and gender roles. By altering the original images Paterson constructs narratives that were often unavailable in the past, opening possibilities for the future.

When speaking of the works “Land, ho!” and “Anchors Away” Paterson says the sea and the nautical endure as symbolically rich and enticing metaphors. Although I have little desire to become physically seaward bound I have imagined a life of sailors, pirates, adventure; storms, shipwrecks, lost at sea; departures, navigation, arrivals.

The accompanying sound piece follows the boy as he sails away from the known world, floating upwards into his own dreamscape. A modified recording of a ship’s bell drones throughout the piece as the sounds of rigging and a boat slicing through water fade in and out.

To view more work by Travis Paterson please visit the Port Jackson Press site.

Listening to G.W. Bot’s “Resurrection Glyph – Midday”.

G.W. Bot is a printmaker based near Canberra. Bot’s work often interprets the essence of the Australian landscape through abstracted forms which she terms “glyphs”. These trace the movement of trees, animals and humans in the landscape, accentuating the spatial dimension that exists between them. Living in close proximity to nature Bot reflects the cycle of life in her work, from birth to death to renewal. The abstracted quality of the glyphs move Bot’s work beyond a merely visual experience, opening them to suggestions of sound.

Resurrection Glyphs – Midday depicts an area ravaged by a bushfire. Blackened tree stumps stand under the unrelenting midday sun, while in the centre a single tree slowly re-emerges from the destruction of the fire. Viewing this print we can imagine the quiet that now pervades the area. Fire continues to crackle in the background, burnt stalks of grass sway in the wind, yet from the resurrected tree crickets and a lone cicada begin to sing.

To view more of G.W. Bot’s work please visit the Australian Galleries website.

Listening to Alexi Keywan’s “The Passenger no.6”.

Alexi Keywan is a printmaker and painter based in Melbourne. Keywan often chooses the urban environment as her subject, interpreting utilitarian scenes through monochromatic colours. Similar to the approach of many field recordists Alexi Keywan is interested in capturing the overlooked urban environment that lies before us, where power-lines connect anonymous buildings to the human world.

This sound composition looks upwards to the power-lines, capturing sounds that emanate from the sky. A helicopter drones in the distance, the sound of traffic floats in the air, and a power-box crackles as rain begins to fall.

To view more of Alexi Keywan’s work from this series please go to this page. An interesting interview with the artist can be viewed here.

Listening to Rona Green’s “Greasy Rhys”.

Greasy Rhys illustrates the hyper-masculinised world of sailors. The piece is typical of Green’s work, depicting a hybrid-figure adorned with a tattoo which clearly depicts the subject’s station in life. An interesting post by Green describes the thought process which resulted in this work.

This sound composition imagines the moment when Greasy Rhys gets his “Last Port” tattoo. At a noisy industrial dockyard he smokes one final cigarette before stepping into a tattoo parlour where he will be forever marked by the iconography of his subculture.

To view more of Rona Green’s work please visit her official site and her blog.

Listening to Jan Davis’ “First Sighting Near Flooding Creek”.

In the 1840s a report concerning a white woman taken captive by an Aboriginal tribe in Gippsland, Victoria, circulated amongst the small colonial population. For years afterwards the story intensified, with the positioning of a single white female forcibly living with the local Aborigines justifying the colonial expansion in the area. Davis’ “First sighting, near Flooding Creek” is part of a series which explores the story in exquisite detail.

In the 1960s a local resident recounted the story of the White Woman, stating “a boat party of five men exploring Lake King saw a lot of wild natives on the shore … Over the top of the sand dune they saw the upper half of the body of a white woman who was trying to press forward to them and was forcibly being held back by Aborigines … the hostile nature of the natives prevented the men from doing anything about it”.

A newspaper from 1840 reported that numerous items of European origin were found at the Aboriginal camp, including children’s clothing, medicines, newspapers, cooking utensils, a bible, and a dead child in a kangaroo skin bag. This emotive imagery effectively reinforced a division between how the two cultures were perceived: the enlightened colonialists, the primitive Aborigines.

The newspaper report confirmed the European belief that the Aborigines were savages who needed to be removed from the white settlements. The gendered positioning of a virtuous white Christian woman in the servitude of Aboriginal men furthered a sense of moral indignation, whilst also providing a sense of titillation for the readers at the time.

Despite several rescue expeditions a white woman was never found, however a figurehead of Britannia taken from a shipwreck was discovered in the possession of the local Aborigines. Was the figurehead the source of the story?

This sound composition interprets Davis’ work by imagining how the unfamiliar sounds of the Gippsland marshlands heightened a sense of trepidation in the early colonialists. The White Woman is out of sight, yet her presence in the mythology of the landscape is palpable.

To view more of Jan Davis’ work from this series please visit Grahame Galleries.

Listening to Julie Barratt’s “The Mourning After”.

Mourning After Blog

Julie Barratt is a printmaker from the northern NSW region of Australia. She is best known for her exhibition concerning grief, The Hankie Project, which investigated the way in which certain objects, specifically handkerchiefs, contain memories of the deceased. 160 handkerchiefs from 12 countries were contributed by artists affected by death, each handkerchief altered to reflect the story of the individual. The handkerchiefs were then pinned to a gallery wall, challenging the silence surrounding grief while celebrating the life of the deceased.

Barratt’s artist book The Mourning After contains scanned images, text and material from The Hankie Project. The hand-stitched pages reveal narratives from individual handkerchiefs, whilst each page is neatly pierced by hundreds of pins in order to symbolise the elusive and painful quality of grief.

This sound composition uses modified recordings of pins slowly dropping onto a plate in Barratt’s studio. The pins were then inserted into the pages of The Mourning After.

To view more about Barratt’s work please visit this site.

Listening to Samuel Tupou’s “Pineapple Princess”.

Samuel Tupou is a print-maker based in Cairns, Australia. Born in New Zealand, and of Tongan heritage, Tupou’s work often combines traditional motifs from his Pacific Islander ancestry with found images from contemporary pop culture. Themes such as westernisation, immigration and personal identity characterise his work.

Pineapple Princess is from Tupou’s 2009 exhibition Somewhere in Time. This silkscreen print is typical of his work, featuring a figure in a bright and surreal landscape. The figure could represent the experience of many immigrant families whose new lives are filled with unfamiliarity and a sense of foreboding dislocation.

This sound composition imagines the way that Pineapple Princess perceives the surrounding landscape and cultural system. Shielded by the motorbike helmet she could be an astronaut on another planet, the sounds she hears belonging to an alien world.

To view more of Samuel Tupou’s work please visit his site.

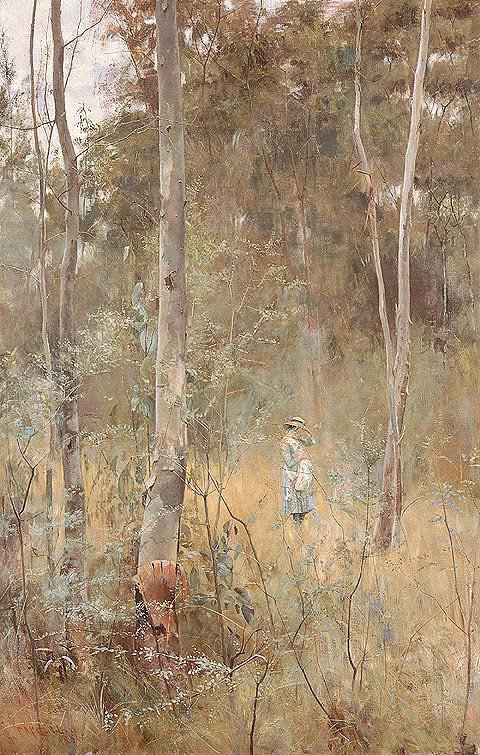

Listening to Frederick McCubbin’s “The Lost Child”.

down on his luck

In the almost trackless wilds of the Lilydale district, intersected by reedy ferns, like an Indian swamp, Clara Crosbie, a girl of 12, was lost nearly a month ago … A town-bred girl of warm affections and quick impulses, she pined in the unaccustomed solitudes of the bush, and she resolved to find her way, though she did not know her way home. The Argus Newspaper. Melbourne, 1885.

Inspired by the true story of Clara Crosbie, Frederick McCubin painted The Lost Child in 1886. In the painting McCubin contrasts the innocence of Clara with the rugged Australian trees which threaten to entrap her. The painting is representative of the early colonial fear which viewed Australia as a place where people disappeared. In the nineteenth century this was a popular theme in literature, particularly in the works of Marcus Clarke, Joseph Furphy, and Henry Lawson. The long distance of Australia from Britain provoked intense feelings of anxiety and was an important part of the colonial experience. Australia was regarded as a country on the edge of the earth and was literally a land where undesirable civilians from Britain were sent to disappear.

This composition overturns the narrative of fear, imagining Clara Crosbie as she briefly becomes entranced by the sounds of the bush. The soft calls of bellbirds and crickets emerge from the trees, providing respite from her predicament. There is a moment of transcendence as Clara finds pleasure in her surroundings, yet home is still far away.

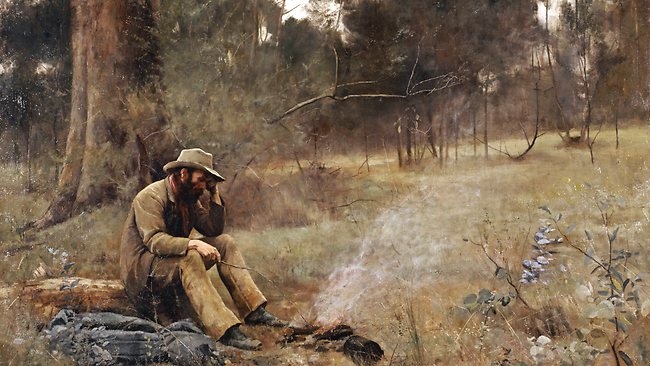

Listening to Frederick McCubbin’s “Down on His Luck”.

During the late 1880s Australia began to formulate a national identity distinct from that of England. A sense of nationalism emerged which questioned the role of England in Australia’s political affairs. As the centenary of Australia’s colonisation drew near this debate was reflected in the art and literature of the time.

Early colonial art often depicted Australia as a replica of the English countryside. This is not surprising when many of the artists were ex-convicts who had been transported to Australia against their will. For them Australia was a country to be suffered while England was still the mother-country. However as the local population grew the cultural relevance of England began to diminish. Artists responded to this shift by emphasising the uniqueness of the Australian landscape in their work. This was especially the case with Frederick McCubin and a group of his fellow artists known collectively as the Heidelberg School.

McCubbin’s Down on His Luck is typical of the art from this period. Painted in 1889 it depicts a gold prospector sitting by a campfire while pensively contemplating his future. The surrounding landscape adds to the melancholic tone. As with much of the artwork from the Heidelberg School the central male figure appears independent and resourceful within the remote rural landscape. Also typical is the absence of women, Aborigines and non-white migrants. The Heidelberg School preferred to celebrate the white male in its narrative, a tradition which continued into the next century.

The National Gallery of Victoria describes the painting’s cultural significance: For city workers, living and working in crowded, dirty conditions, McCubbin’s image of the prospector offered an alternative to the oppressive poverty experienced in the slums of Melbourne. Although the bushman is ‘down on his luck’, he has a certain nobility. He is his own man, independent of the demands of a ‘boss’, he breathes the fresh air of the bush and is free to make his own decisions. The sensibilities portrayed in this painting continue to capture Australia’s national spirit, though the majority of the population now live in urban centres far removed from the bush.

This composition interprets the soundscape immediately surrounding the prospector. A small campfire crackles while birds and cicadas call from the trees.

Listening to Haughton Forrest’s “Ships in a Storm”.

Haughton Forrest was a French born artist who immigrated to Australia in 1881. Forrest’s paintings of wild stormy seas and tranquil countrysides belong to the aesthetic of the Romantic Period. Ships in a Storm is typical of his portrayal of the ocean as an inhospitable space which refuses to be tamed by human activities.

Ships in a Storm follows in the lineage of other Romantic artists, such as Turner and Delacroix, who chose to depict scenes of boats in peril. In this early industrial era there was a general feeling of nostalgia for the past, with many artists and writers reflecting upon the precariousness of a society which was losing contact with nature.

This sound composition moves from the breakwater and climbs aboard both boats as they sway and creak in the rough sea. Bells ring from the boats indicate their proximity to each other. Here sound acts as a guide in the darkness of the storm.

Listening to Rodney Pople’s “Port Arthur”.

In March 2012 Rodney Pople won the Glover Prize, Australia’s most prestigious landscape painting award, for his work “Port Arthur”. Pople’s depiction of Port Arthur uses a classical style to blur the site’s colonial and modern histories. Controversially Pople included a small figure in the foreground, that of mass-murderer Martin Bryant.

On the 28th April 1996 Martin Bryant entered the historic site of Port Arthur with a semi-automatic rifle. After setting-up a video camera on a cafe table Bryant proceeded to shoot patrons and staff. By the end of the rampage 35 people were dead, 21 had been wounded. Bryant is now serving 35 consecutive life sentences in prison.

For those who survived that day the judge’s decision to award Pople with the first prize was marked as dubious and insensitive. Pople is now the object of intense debate with his detractors claiming the placement of the figure in the painting glorifies Bryant. In his defence Harrington writes Pople’s painting presents the landscape as being more than just bucolic beauty. It expresses the idea that our darkest histories are indelible stains on our landscape – its scars. In response to the debate Pople has said Bryant is sort of fading into the distance compared to the power of the whole landscape but he is part of it. I am not in any way glorifying Martin Bryant but to ignore it is looking in the wrong way as well.

On a recent trip to Port Arthur it was impossible to disregard the events from 1996. Walking amongst the ruins and the open lawns it was easy to feel Bryant’s presence looming over the picturesque site. Inspired by the British National Gallery’s sound programme this composition interprets Pople’s painting through the use of field recordings, most of them taken at Port Arthur.

You can visit Pople’s site here.

seriously awesome work dude, these soundscapes are tremendous! they truly do bring the art to life…

LikeLike

Nice work!

LikeLike

Thanks, you might like some of the posts promoting my exhibition “Auditory Visions”.

LikeLike